First off, Dan Flavin. It's kinda funny because Flavin used to be my case in point for some contemporary art that's, how shall I put it, Insincere. I would, in particular, point to one of his single light bank installations and call B.S. The thing is though, I stumbled upon a collection of his work in an old church in Bridgehampton that is now a permanent collection of his pieces and I was blown away. I was actually able to understand what it is he's doing, or at least, get a glimpse of it, in my own way, and boy did it make a difference.

Click here. All that being said, I'm still not a fan of some of his smaller, simpler, installations. To me, they're still just lightbulbs.

Click here. All that being said, I'm still not a fan of some of his smaller, simpler, installations. To me, they're still just lightbulbs.

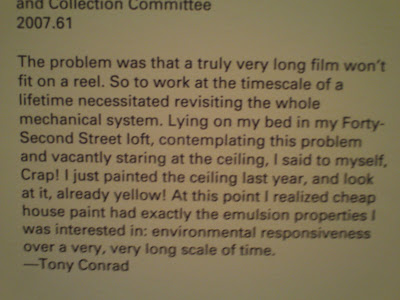

I really like the idea behind this one, using one's ceiling as an extralong movie or long exposure painting. Great.

Robert Irwin. This guy is fantastic. His pieces distort the mind and create this blurry/ soft focus unreality. They have to be experienced, but you can catch a glimpse in the photo above. It's really hard to know where one piece ends and the next starts. Somehow this feeling gets into your body, and everything in the world begins to merge. Can you see the light glare on the upper right of the circle? It brings another dimension, no? Now factor in that you can't possibly experience this piece from my picture. Or maybe, you can have an experience, but definitely not seeing it in person...

Sadly, I don't know who did this. But so what. I loved looking at it and figuring it out. Clearly the glass was brought in whole, and then broken on site. There were still miniscule little slivers on the floor. It's site specific nature, (Although now that I say it, is it site specific?) I was going to say, it's site specific nature brings up many questions. But theoretically, it could be done anywhere, however, it can't truly be moved and still carry the original power of the truth from impact. Well anyway, it does a good job of communicating the energy of the impact, and the energy inherent in the glass which is then displayed in it's shatter.

On the bottom, you can see there is one piece sticking out from the "frame" created by the top pane of glass. Did that happen naturally or was it pulled out? If so, why? What is the effect?

Edward Ruscha

Chocolate Room

1970/2004

For its debut at the 35th Venice Biennale in Italy, Chocolate Room originally consisted of 360 shingle-like sheets of paper silk-screened with chocolate and applied to the interior walls of the gallery space. Edward Ruscha was just starting to work with organic materials in his prints, using such unconventional substances as blood, gunpowder, or cherry juice instead of traditional inks. During the summer of 1970, curator Henry Hopkins invited Ruscha and several other artists to make a work for the American Pavilion as part of a survey of American printmaking with an on-site workshop. Many declined the invitation in protest against the Vietnam War; Ruscha intended to do the same, but eventually reconsidered. When Chocolate Room went on view in Venice, protesters etched anti-war slogans into the rich brown surfaces of Chocolate Room, leaving it to stand as a spontaneous anti-war monument, which Ruscha ultimately considered more effective than non-participation in the Biennale. In the summer heat, the heady smell of chocolate was particularly overwhelming and attracted a swarm of Venetian ants, which ate away at the work. MOCA acquired Chocolate Room in 2003 and silk-screens new chocolate panels each time it is installed.

So, more questions... How does one acquire something that doesn't exist? If every time it is displayed, it is re-silk-screened, then is it the same piece? What's to stop someone else from doing the same thing. Can they call it an Ed Ruscha piece? Does every museum in the world own this piece the moment they silk-screen and hang the pieces?

2 comments:

That's an interesting question about the Ruscha piece. I'm trying to write a paper about conservation of food art and was wondering about that too. From what I could gather ''Chocolate Room'' was created for the American pavilion at the 35th Venice Biennale (1970)It was shown again in 1995 for ''1965-1975: Reconsidering the Object of Art,'' a survey of Conceptual art at the Los Angeles museum. After that ''Chocolate Room'' went back to the artist, who sold it to the museum. In a 2004 article I read, it said that the museum was only silkscreening pieces to replace broken, cracked and crusty ones. If that's the case I guess you could argue that it's only a restoration of the original not an entirely new recreation.

The impression I got, was that it's redone entirely every time. I don't take issue with this, I don't think it takes away from the "Authenticity" of the piece, but at the same time, I feel it almost makes the work itself public domain. How can the idea of silkscreening Chocolate on paper be "sold" to a museum? As far as I'm concerned, why couldn't I do the work, call it "after Ed" and sell it to a museum.

And no, this isn't the "My six year old could do that" arguement. I'm asking these questions to investigate, not to instigate.

Post a Comment